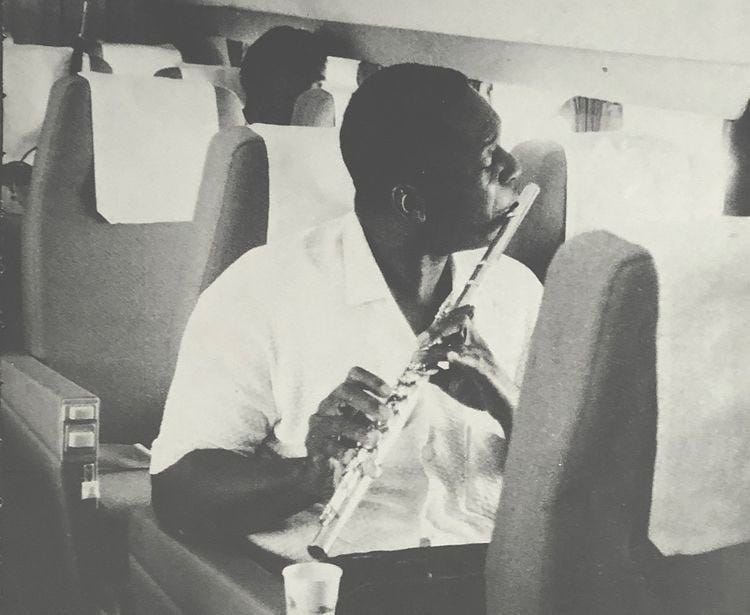

For two weeks, my worst nightmare came true: I awoke one morning from uneasy dreams and found myself transformed into someone without flute-playing lips.

Nothing above the staff was sounding, and everything below it was out of tune. This is a major insecurity, for I never really learned how to make a sound on the flute. I produced a pretty decent tone on my first try at the instrument petting zoo, and that’s mainly why I picked it.

Without recourse to actual methods, I resorted to arcane lip remedies, alternated between debauchery and asceticism, and contemplated a life without music. Turns out my flute just needed oiling. Let that be a lesson for any traverso players out there: oiling is like restarting the computer or blowing on the Game Boy cartridge.

It’s funny how much of my life goes to shambles when the playing isn’t going well. Without my flute, I’d surely have been found in a ditch somewhere. I briefly consider learning how to be an adult sans flute—but I’d rather keep playing.

If I ever take up the modern flute again, it will be to play jazz.

Quantz opens his treatise On Playing the Flute not with anything prosaic about the instrument, but with an essay on “The Qualities Required of Those Who Would Dedicate Themselves to Music.” I spent the afternoon mulling over this remarkable passage from it, on the state of music in Germany c. 1750. I quote it at length because it is still true today, and I imagine it will always be so. Mutato nomine de te fabula narratur—change only the name, and the story applies to you.

Furthermore, he who wishes to excel in music must feel in himself a perpetual and untiring love for it, a willingness and eagerness to spare neither industry nor pains, and to bear steadfastly all the difficulties that present themselves in this mode of life. Music seldom procures the same advantages as the other arts, and even if some prosper in it, this prosperity is most often subject to inconstancy. Changes of taste, the weakening of bodily powers, vanishing youth, the loss of a patron—upon whom the entire fortune of many a musician depends—are all capable of hindering the progress of music. […] At many courts, and in many towns where music previously flourished, so that a good number of able people were trained in it, now nothing but ignorance prevails. At the majority of courts formerly provided with some moderately able people, and even with some very celebrated ones, the unfortunate custom has been introduced of giving the first places in the musical establishment to persons who do not merit even the last positions in a good orchestra, to persons whose office does indeed bring them some consideration among the ignorant who allow themselves to be blinded by titles, but who do no honour to their office, bring no advantage to music, and do not advance the pleasure of those upon whom their fortune depends. Although music is a science that can never be studied and invesstigated too thoroughly, it does not have the good fortune of other sciences, in part higher, in part on the same level, of being taught publicly. Some cloudy-minded modern philsophers do not, like the ancients, consider knowledge of it a necessity. People of means do not cultivate it, and the poor do not have the means to retain good masters at the outset, or to travel to places where music of good taste is in vogue. Nevertheless, at some places music has again begun to receive greater esteem. There once more it has its noble connoisseurs, protectors, and patrons. Its honour is beginning to be restored by those enlightened philosophers who again count it among the fine arts. The taste for these fine arts, particularly in Germany, is becoming increasingly enlightened and widespread. Those who have decent training can always earn a living.

How heartening. There has never really been a good time to be a musician.

OH my that's beautiful. PS, It took you two weeks to oil your flute???